What is the Opioid Epidemic? A public health explainer

By Cassie Sun

May 28, 2024

[This article is an installment in our ongoing series: Public Health Topics Explained.]

IntroductionThe opioid epidemic is an ongoing public health crisis that has affected millions of people in the United States over the past two decades. Officially declared a Public Health Emergency by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in 2017, the epidemic has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Americans.

While the roots of the epidemic are complex, many agree that its origin can be traced to the late 1990s when the increased availability of prescription opioid pain killers led to a spike in opioid use disorder, a pattern of opioid use leading to “impairment or distress.” In some cases, the disorder can lead to overdose and death.

Opiates, opioids, narcotics: what’s the difference?Opioids are a broad category of drugs that interact with receptors in the brain to interfere with or dampen pain. They include both prescription medications such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine; and illegal substances such as heroin.

The term “opioids” encompasses natural chemical compounds as well as synthetic and semisynthetic compounds made in a lab, such as fentanyl.

The term opiates refer only to naturally derived opioids including heroin, morphine and codeine.

The term narcotics originally indicated any substance that “dulled the senses and relieved pain.” While some people still use the term to refer to all illegal drugs, “opioid” is now the preferred term for both legal and illegal substances.

The four waves: how opioid use became an epidemic.

Over its history, the opioid epidemic has moved through four phases, or “waves.” These waves are overlapping, creating epidemics within epidemics.

The first wave of the opioid epidemic began in the 1990s with an increase in opioid prescriptions, which included natural and semi-synthetic compounds. Physicians prescribed medication for non-cancer-related pain as well as for chronic pain, creating greater opportunities for addiction. The most commonly prescribed opioids included oxycodone and hydrocodone, also known as OxyContin and Vicodin. OxyContin in particular, released by Purdue Pharma in 1995, was marketed as a less-addictive, more mild form of opioid. The aftermath of the first wave manifested in the doubling of the rate of opioid-related deaths in the U.S. from 1999 to 2010.

The second wave extended from 2010 through 2013 and was marked by a rapid increase in heroin overdose deaths. It’s believed that one major contributor to the increase was the effort to curb prescription-related overdoses, which led to a large population of people dependent on prescription opioids to take up heroin as an alternative. Heroin, a highly addictive drug made from morphine, is dangerous on its own. When used in conjunction with other drugs or alcohol, its danger is multiplied. From 2002 to 2013, rates of overdose by heroin nearly quadrupled in the U.S. The second wave was prompted by the heroin market, which “expanded to attract already addicted people.”

The third wave began in 2013 and was characterized by an increase in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids, particularly fentanyl. Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. While fentanyl is occasionally used in health systems for surgical procedures, fentanyl-related overdoses primarily occur from illegal forms of the drug.

The latest phase of the opioid epidemic, the fourth wave, is still ongoing. It’s distinguished by the increased use of multiple substances at once, specifically, the combined use of cocaine or methamphetamine plus fentanyl. This was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which time opioid overdoses increased, with 80,411 overdose deaths recorded in 2021, accounting for over 75% of all overdose deaths.

Researchers from Northwestern University’s Institute for Public and Medicine believe the fourth wave is distinct because it is no longer affected by geography. While opioid overdose deaths for the previous three waves followed geographic trends, the new wave is predicted to be experienced by rural and urban counties at similar rates of increase.

“The big takeaway is that opioids and drug overdose deaths were largely confined to urban populations until a rise in overprescription created a cohort of opioid-dependent Americans in rural communities,” said Lori Post, PhD, director of the Buehler Center for Health Policy and Economics and professor of emergency medicine.

“For the first time since the Civil War, opioid overdose deaths did not “move” into the rural areas, but a new independent outbreak began in rural areas until the death rate exceeded those in urban areas. This was the result of overprescribing semisynthetic opioids. Every time a new wave of opioids would sweep America, it would cause an acceleration, but urban and rural areas were not in sync until the fourth wave.”

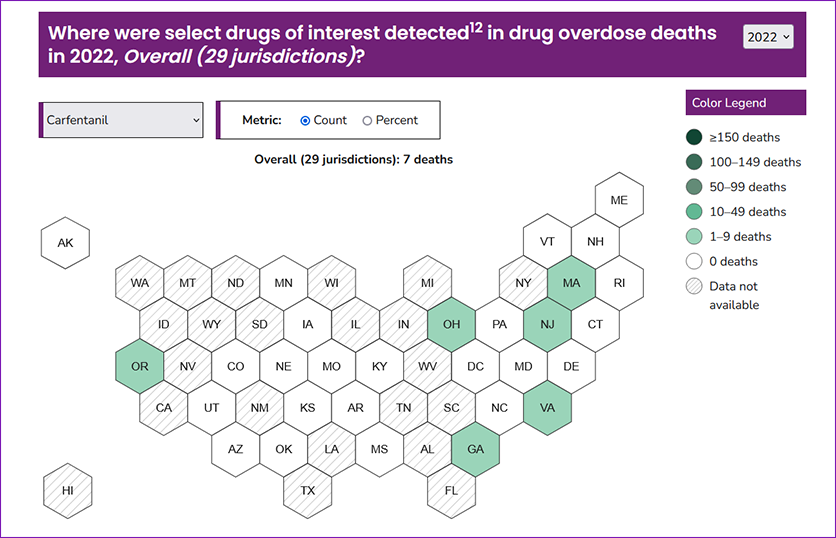

Who is affected by the crisis?The CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) reported 51,435 total overdose deaths in 2022. Males are more likely than females to die of a drug overdose, as are people aged 35-44. American Indian/Alaska Native and non-Hispanic have the highest death by drug overdose rate by race/ethnicity.

Northwestern researchers have similarly compiled a public dashboard centering drug overdose information specific to Illinois. The dashboard contains comprehensive demographic trends, such as the rapid increase in older adults (55-64 years old) and non-Hispanic Black adults involved in overdose deaths.

“My hope is that these data can be used to inform prevention work. That could include resource allocation decision-making, messaging, targeting audiences and intervention development, implementation and evaluation,” said Maryann Mason, PhD, associate professor of emergency medicine.

Tackling the opioid epidemicDozens of organizations and hundreds of researchers across the country have been working to understand and address the epidemic. Public health officials have turned to harm-reduction approaches to combat the opioid overdose crisis. Below are some of the most recent programs being levied against the crisis.

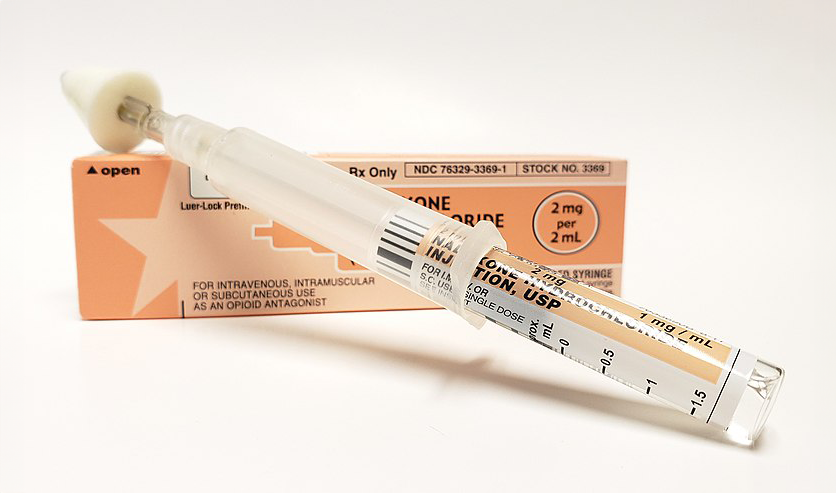

Opioid Overdose Reversal Medications (OORM)Opioid Overdose Reversal Medications are a class of drugs designed to safely reverse an opioid overdose. One of the most prominent OORMs is Naloxone, also known as Narcan. Naloxone works by binding to opioid receptors, thereby stopping opioid uptake in the brain. It was approved for over the counter sales by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in March 2023. Naloxone temporarily counters the effects for someone showing signs of overdose. Naloxone can be administered as a nasal spray or an intramuscular injection. However, it is a temporary medication that only stays in the body between 30 to 90 minutes. Thus, it's critical to call 911 after administering a dose.

Availability of naloxone has grown in recent years, and can now be found free at some government offices and even public libraries. The Illinois Department of Public Health recently updated an order that allows school officials to administer naloxone in case of opioid overdose, expanding access to critical medication.

Harm Reduction Movement

Harm reduction focuses on using public health strategies such as "prevention, risk reduction, and health promotion" to minimize negative health, social and legal impacts associated with drug use. The movement specifically centers on providing resources including overdose counseling, distributing test strips and OORMs such as naloxone, and referrals to health services.

"Block by Block" is an overdose fatality prevention initiative led by Mason. The project uses data from SUDORS to identify areas of high overdose and deploys community outreach workers to go door-to-door in these communities to offer naloxone, fentanyl and xylazine test strips and training on how to use them. The evidence-based intervention aims to target overdose hotspots and have an "immediate impact in reducing drug overdose fatalities in these areas by increasing community knowledge, access to resources, and interconnectedness."

Medication and the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment Act (MAT Act)In conjunction with behavioral treatments for opioid use disorder, the FDA has reported on the effectiveness of medication-assisted treatment that can prevent intense cravings. Specifically, three drugs have been approved by the FDA as treatment: buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone. A recent law, the MAT Act, advocates for greater access to treatment for opioid use disorder by allowing licensed healthcare professionals to prescribe the approved medications without specialized training. By integrating medical treatments for the disorder into primary care and other settings, more patients can maintain recovery from opioid dependence.